227. Tough times: 1941 and 1942

The years 1941 and 1942 were tough ones… Things were going badly in the Battle of the Atlantic, with Germany threatening to strangle Britain by sinking more merchant ships than the British could bear to lose. In the Far East, the Japanese were giving the British, and indeed several other of the western nations previously seen as unbeatable, that they could be beaten by an Asian power. But by taking on the Americans, they’d made a mistake: the US had barely deployed its strength and, when it did, it first put a stop to Japanese advance by sea or land before it started to fight back. In Russia too, the German advance was running out steam. Unexpectedly tough resistance from the Soviets stopped the Germans short of their objectives. One army made it as far as the city now called Volgograd, then called Stalingrad. What happened to it there is something for our next episode. Meanwhile, in North Africa, late 1942 was when Rommel’s breathtaking advance was at last halted at the First Battle of El Alamein in Egypt, by General Claude Auchinleck at the head of the British Eighth Army. Sadly, though, that hadn’t come fast for Winston Churchill or the British Chief of Imperial General Staff, who relieved Auchinleck of his command. Credit for the victory would go to someone else. Again, a story for the next episode. Illustration: Officers on the bridge of a British destroyer escorting a convoy of ships, looking out for submarines. Public Domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

19 Tammi 14min

226. Britain rescued by its enemies

Hitler, feeling himself obliged to help out his inept ally Mussolini, was dragged into two wars the Italian dictator had started but lacked the resources to prosecute to victory: in North Africa and in Greece. Where the Italians had failed, the Germans moved in with lightning speed, overrunning Yugoslavia and Greece, and driving the hitherto triumphant British into retreat in Libya. Britain meanwhile was feeling the pain of a German blockade, most effectively applied by submarines, the deadly U-boats of the German navy. Britain was stepping up its bombing of Germany (while also continuing to be bombed back itself), in the deluded belief that this might win the war. That limited its ability to extend air protection to convoys of ships crossing the Atlantic, where it came close to losing it. Then in June 1941, Germany made a colossal error. Despite having committed forces in North Africa and the Balkans, it went ahead with Hitler’s pet project, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Suddenly Britain, previously without great power allies, found the Soviets dragged into fighting the Germans too. In December, Japan made an equally massive mistake, attacking the US in an air raid of Pearl Harbor. Now the US declared war on Japan and, when Germany in solidarity with its Axis partner in the Far East, declared war on the US, Britain found itself with another mighty partner in its war effort. It was a huge turnaround for Britain. Obtained not though its own efforts, though Churchill had done all he could to persuade the US into the fighting, but through the errors of its enemies. A failing with plenty of precedents in history… Illustration: Contemporary photo of the attack on Pear Harbo. Public Domain. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

12 Tammi 14min

225. Blitz

Following the Battle of France, came the Battle of Britain. Thanks, though, above all to the fighter pilots of the RAF – 20% of them from other countries, led by Poland and New Zealand – Britain weathered that storm, where France had been overcome by it. There’d been fewer than 3000 of those airmen but Britain owed its survival in the war to them so, as Churchill put it, never ‘was so much owed by so many to so few’. But Britain was far from out of the woods yet. There were worrying signs from the Far East where, taking advantage of France’s defeat, Japan had occupied the north of Vietnam, then part of the French colony of Indochina. Its aim in doing so was to cut off a supply route to the Nationalist forces fighting the Japanese army in China, but it also brought Japan right up to the imperial territories of the European powers with holdings in the region: as well as France these were Britain, with its holdings in India and Malaya, as well as Holland in the Dutch the East Indies. Meanwhile, there was fighting in North Africa too, where the British overwhelmed the Italians attacking from Libya into Egypt. But then Rommel showed up with the German Afrika Korps. The tables were about to be turned. Illustration: A German Luftwaffe Heinkel He 111 bomber flying over the East End of London on 7 September 1940. Photo from a German aircraft. Public Domain. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

5 Tammi 14min

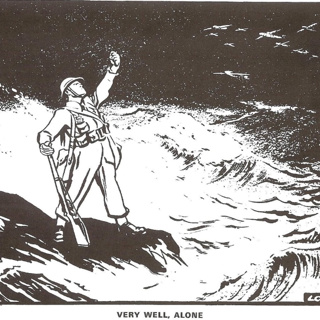

224. Very well, alone

The phoney war’s over. The shooting war has begun. And it isn’t going at all well. France is in collapse, its generals quickly turning defeatist and its politicians unable to shake them out of their inertia. Churchill tried hard, flying across to talk them into keeping up the fight, but without success. In the end, they surrendered to the Germans, being forced to sign an armistice in the same railway wagon, in the same forest, where they had previously forced the Germans to sign their armistice at the end of World War One. Britain was now more isolated than ever. Not as alone as many liked to think, since it had its empire and dominions still with it, and they supplied huge numbers of men. But without either of the growing world powers, the US or the Soviet Union. Now Churchill had to become tougher than ever. First, he had to see off Halifax, his own defeatist, serving in his war cabinet. Fortunately, he had the support of the Labour members, and the man invited as a guest, the Liberal leader too. When Chamberlain finally came down on his side, Churchill, buoyed by the success of the Dunkirk evacuation, could see off Halifax. Next, he had to show that he had the hard core, the ruthlessness even, to win the war. He did that but in a tragic action, the firing by British warships on a French fleet in Mers el-Kébir, in Algeria. The major loss of life among men who’d been allies weeks earlier was a bitter pill for everyone to swallow. Arguably, though, it prepared the British to develop the toughness for the harsh trial that was about to start. As Churchill warned, Hitler had now to turn his ‘whole fury and might’ on them. That’s the subject of next week’s episode. Illustration: ‘Very well, Alone’, cartoon by David Low, June 1940. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

29 Joulu 202414min

223. Blood, toil, sweat and tears

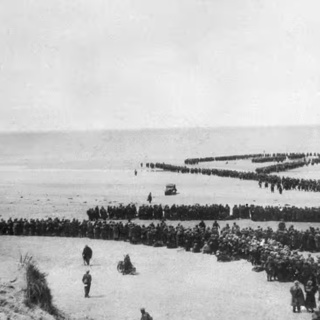

This episode includes several extracts from recordings of speeches by Churchill, so that we can enjoy listening to his actual voice – on the other hand, I apologise for the background noise on the recordings, but they sound inauthentic if I try to remove it. We also meet a number of people who will continue to have a significant role later: a man who deserves to be better-known, the brilliant theoretician and practitioner of armoured warfare (sadly on the German side), Heinz Guderian; Erwin Rommel; Charles de Gaulle; Friedrich Pauls, attending an enemy’s surrender now though better known for offering his own later; and Bertram Ramsay, another man who deserves to be far better known than he now is. All this is against the background of the devastating defeat of British and French forces in France, once Germany decided to end the phoney war (which had already started to be a lot less phoney in Norway) and, using the Blitzkrieg tactics favoured by Guderian, of rapidly-advancing armoured forces backed by air support and followed by infantry, broke though the French defences and rounded on the British Expeditionary Force and French troops in Northeastern France, pinning them against the Channel coast. Those Allied troops were caught in a vice that was closing on them. It was only the extraordinary ability of the man Churchill chose to organise their evacuation from Dukirk, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, and Churchill’s own leadership, that allowed Britain to save the core of its army from destruction. Illustration: Troops waiting to be taken off the beaches at Dunkirk. Photo: EPA. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

22 Joulu 202414min

222. All behind you, Winston

Britain, along with France, might well have declared war against Germany in September 1939. But that didn’t lead to much fighting for the next eight months. There was some action at sea, during which the British Royal Navy put an end to German surface raiders, though it had still to face the worst threat to its maritime trade, which came not from ships on the surface, but from submarines. On land, in the west, there was practically no action, in what came to be known as ‘the phoney war’. It wasn’t phoney for the Poles of course, who were being bombed and invaded, first only by the Germans from the west, but soon by the Soviets from the east too, rather confirming what many suspected, that the Nazi-Soviet pact included a secret protocol dividing up Poland between the two countries. The Pact also provided the Soviets with the confidence to invade Finland which they did at the end of November. Britain and France decided to come to the Finns’ aid by landing troops at the Norwegian port of Narvik, but it took them so long that Finland had been defeated, after some heroic resistance, before the Allies could help. However, the Allies went on with the idea of landing at Narvik,to cut Germany’s supplies of iron ore from Sweden, most of which went through the port. Unfortunately, they took so long and were so indiscreet in their plans, that Hitler pre-empted them, invading and occupying Denmark and southern Norway, and getting troops to Narvik first, able to resist the Allied landings when they finally happened. Though marginal in itself, the Narvik fiasco prompted a major debate in the British House of Commons, in which the government, although it won a final vote of confidence, did so with so small a majority that Chamberlain felt major changes had to be made. He decided it was time to form a national government, in coalition with Labour and the Liberals. That, though, proved impossible to pull off if he stayed on as Prime Minister. He stood down and, as the front runner to replace him, Halifax, said he wasn’t prepared to take the post, it inevitably fell to Winston Churchill to shoulder the burden. Labour and the Liberals joined him. So it was together behind him, as depicted by David Low in a new cartoon, that they faced the next, far worse crisis that was about to hit Britain and France. Illustration: ’All behind you, Winston’, cartoon by David Low, May 1940. In the front row from left: Churchill, Attlee, Ernie Bevin and Herbert Morrison. Behind Churchill is Chamberlain. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

15 Joulu 202414min

221. 1939 turns truly shocking

Between 1938 and 1939, Churchill went from pariah and opponent of the Prime Minister, to the man of the moment many were calling on to re-enter government. That reflected the gradual realisation that Churchill had been right in warning of the need to resist Hitler and of approaching war, while Chamberlain had been wrong to think he could preserve peace by appeasing the dictators. By the end, Chamberlain had actually gone so far as to ask Churchill whether he would join a war cabinet, though not so far as to offer him an actual post, when Churchill said he would. That was on 2 September 1939. By then, German troops were rolling across Poland, while their aircraft were bombing Polish cities. MPs were beginning to lose patience with Chamberlain, who was still talking about proposals to preserve the peace, when most were increasingly convinced that war was inevitable. It even reached the stage when, the same evening, a fellow Tory, Leo Amery, disgusted with Chamberlain’s statement, called on Arthur Greenwood, the Labour spokesman of all people, to ‘Speak for England’. The next day, Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany. Illustration: Chamberlain broadcasting the news of war with Germany to the nation, 3 September 1939. BBC photograph. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

8 Joulu 202414min

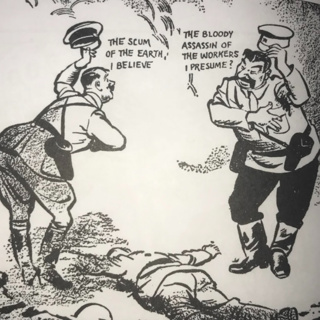

220. Second biggest shock of 1939

The Munich Agreement had bought peace. But at a price. The highest had, of course, been paid by Czechoslovakia which lost much of its territory. But there was also a cost in the increasing distrust of the Soviet Union, another of the protecting powers of the Czechs, which had simply been left out of the Munich negotiations, towards the Western Powers. In Britain, though, Chamberlain enjoyed a burst of popularity, as the man who’d preserved the peace. It would be short-lived, however, as the enormity of the betrayal of the Czechs sank in. And after the sheer horror of the pogrom across Germany known as Kristallnacht, there was a swing against appeasement and against the government. That became stronger after Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. The invasion in effect tore the Munich Agreement to shreds. Now the pressure for a strong stance against Hitler, and in particular to come to an agreement with the Soviet Union to help, became too powerful for Chamberlain to resist. But the British conducted negotiations with the Soviet Union in such a casual way, so dismissively of the Soviets, that failure was unavoidable. Within days of the collapse of the negotiations, the Soviet Union announced that it had signed a Non-Aggression Pact with the Nazi Germany. This was one of the most shameful international agreements ever signed. But Britain’s stance had contributed to it. What’s worse, the pact, the second biggest shock of 1939, would lead within a week to the biggest of all. Which we’ll tackle, appropriately, in a week’s time. Illustration: David Low, ‘Rendez-vous’. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

1 Joulu 202414min