223. Blood, toil, sweat and tears

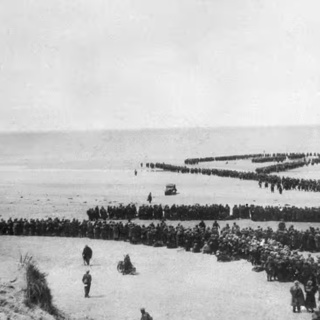

This episode includes several extracts from recordings of speeches by Churchill, so that we can enjoy listening to his actual voice – on the other hand, I apologise for the background noise on the recordings, but they sound inauthentic if I try to remove it. We also meet a number of people who will continue to have a significant role later: a man who deserves to be better-known, the brilliant theoretician and practitioner of armoured warfare (sadly on the German side), Heinz Guderian; Erwin Rommel; Charles de Gaulle; Friedrich Pauls, attending an enemy’s surrender now though better known for offering his own later; and Bertram Ramsay, another man who deserves to be far better known than he now is. All this is against the background of the devastating defeat of British and French forces in France, once Germany decided to end the phoney war (which had already started to be a lot less phoney in Norway) and, using the Blitzkrieg tactics favoured by Guderian, of rapidly-advancing armoured forces backed by air support and followed by infantry, broke though the French defences and rounded on the British Expeditionary Force and French troops in Northeastern France, pinning them against the Channel coast. Those Allied troops were caught in a vice that was closing on them. It was only the extraordinary ability of the man Churchill chose to organise their evacuation from Dukirk, Admiral Bertram Ramsay, and Churchill’s own leadership, that allowed Britain to save the core of its army from destruction. Illustration: Troops waiting to be taken off the beaches at Dunkirk. Photo: EPA. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

22 Dec 202414min

222. All behind you, Winston

Britain, along with France, might well have declared war against Germany in September 1939. But that didn’t lead to much fighting for the next eight months. There was some action at sea, during which the British Royal Navy put an end to German surface raiders, though it had still to face the worst threat to its maritime trade, which came not from ships on the surface, but from submarines. On land, in the west, there was practically no action, in what came to be known as ‘the phoney war’. It wasn’t phoney for the Poles of course, who were being bombed and invaded, first only by the Germans from the west, but soon by the Soviets from the east too, rather confirming what many suspected, that the Nazi-Soviet pact included a secret protocol dividing up Poland between the two countries. The Pact also provided the Soviets with the confidence to invade Finland which they did at the end of November. Britain and France decided to come to the Finns’ aid by landing troops at the Norwegian port of Narvik, but it took them so long that Finland had been defeated, after some heroic resistance, before the Allies could help. However, the Allies went on with the idea of landing at Narvik,to cut Germany’s supplies of iron ore from Sweden, most of which went through the port. Unfortunately, they took so long and were so indiscreet in their plans, that Hitler pre-empted them, invading and occupying Denmark and southern Norway, and getting troops to Narvik first, able to resist the Allied landings when they finally happened. Though marginal in itself, the Narvik fiasco prompted a major debate in the British House of Commons, in which the government, although it won a final vote of confidence, did so with so small a majority that Chamberlain felt major changes had to be made. He decided it was time to form a national government, in coalition with Labour and the Liberals. That, though, proved impossible to pull off if he stayed on as Prime Minister. He stood down and, as the front runner to replace him, Halifax, said he wasn’t prepared to take the post, it inevitably fell to Winston Churchill to shoulder the burden. Labour and the Liberals joined him. So it was together behind him, as depicted by David Low in a new cartoon, that they faced the next, far worse crisis that was about to hit Britain and France. Illustration: ’All behind you, Winston’, cartoon by David Low, May 1940. In the front row from left: Churchill, Attlee, Ernie Bevin and Herbert Morrison. Behind Churchill is Chamberlain. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

15 Dec 202414min

221. 1939 turns truly shocking

Between 1938 and 1939, Churchill went from pariah and opponent of the Prime Minister, to the man of the moment many were calling on to re-enter government. That reflected the gradual realisation that Churchill had been right in warning of the need to resist Hitler and of approaching war, while Chamberlain had been wrong to think he could preserve peace by appeasing the dictators. By the end, Chamberlain had actually gone so far as to ask Churchill whether he would join a war cabinet, though not so far as to offer him an actual post, when Churchill said he would. That was on 2 September 1939. By then, German troops were rolling across Poland, while their aircraft were bombing Polish cities. MPs were beginning to lose patience with Chamberlain, who was still talking about proposals to preserve the peace, when most were increasingly convinced that war was inevitable. It even reached the stage when, the same evening, a fellow Tory, Leo Amery, disgusted with Chamberlain’s statement, called on Arthur Greenwood, the Labour spokesman of all people, to ‘Speak for England’. The next day, Chamberlain announced that Britain was at war with Germany. Illustration: Chamberlain broadcasting the news of war with Germany to the nation, 3 September 1939. BBC photograph. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

8 Dec 202414min

220. Second biggest shock of 1939

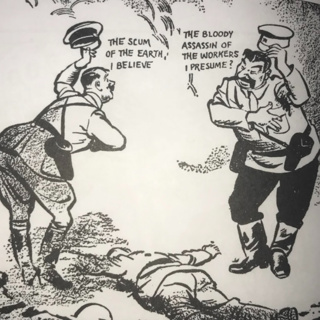

The Munich Agreement had bought peace. But at a price. The highest had, of course, been paid by Czechoslovakia which lost much of its territory. But there was also a cost in the increasing distrust of the Soviet Union, another of the protecting powers of the Czechs, which had simply been left out of the Munich negotiations, towards the Western Powers. In Britain, though, Chamberlain enjoyed a burst of popularity, as the man who’d preserved the peace. It would be short-lived, however, as the enormity of the betrayal of the Czechs sank in. And after the sheer horror of the pogrom across Germany known as Kristallnacht, there was a swing against appeasement and against the government. That became stronger after Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. The invasion in effect tore the Munich Agreement to shreds. Now the pressure for a strong stance against Hitler, and in particular to come to an agreement with the Soviet Union to help, became too powerful for Chamberlain to resist. But the British conducted negotiations with the Soviet Union in such a casual way, so dismissively of the Soviets, that failure was unavoidable. Within days of the collapse of the negotiations, the Soviet Union announced that it had signed a Non-Aggression Pact with the Nazi Germany. This was one of the most shameful international agreements ever signed. But Britain’s stance had contributed to it. What’s worse, the pact, the second biggest shock of 1939, would lead within a week to the biggest of all. Which we’ll tackle, appropriately, in a week’s time. Illustration: David Low, ‘Rendez-vous’. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

1 Dec 202414min

219. Hitler bouncing his Czechs

With the Austrian annexation complete, Hitler could now start eying up his next target, Czechoslovakia again. Although Italy had proved absolutely no help to Britain in trying to stop Hitler’s move against Austria, Chamberlain had given his word to put in place an agreement which would accept the Italian occupation of Abyssinia in return for some Italian commitments in the Mediterranean, over the Suez Canal, and to stop intervening in the Spanish Civil War. Chamberlain seems to have felt that he had to go ahead with this agreement and submitted it to the Commons for approval. With Conservative anti-appeasers rather muted, even Churchill, the opposition had to be led by Attlee. He was Leader of the Opposition, which was now oddly enough a paid post. He had also strengthened his position in the Labour Party, especially since two colleagues, Bevin and Dalton, had forced through a change of policy to stop opposing the government’s plans for defence spending – they felt that such expenditure was increasingly needed in the face of the growing threats from the dictatorships. Attlee also spoke out loudly in defence of the Spanish Republic, especially after a visit there in late 1937. The House of Commons approved the agreement with Italy despite the opposition to it. That in effect turned a blind eye to Italy’s breach of international law in Abyssinia. Now Hitler prepared his next breach of such law. Faced with what seemed to be an imminent Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia, Chamberlain travelled out to see Hitler three times, on the last occasion accompanied by the French Prime Minister, Daladier, and the Italian dictator, Mussolini. The resulting Munich Agreement, which allowed Germany to absorb a huge part of Czechoslovakia, on the pretext of protecting the German-speaking minority in those areas, left the country defenceless to future attack. In the parliamentary debate on the Agreement, Churchill emerged as the champion of the anti-appeasement cause, though Attlee too spoke out powerfully against it. But there was relief across the country and in most parts of the House of Commons that peace had apparently been preserved. That left the anti-appeasers swimming against the current of public and political opinion. The peace that Chamberlain had bought would, however, not last long. Illustration: Chamberlain waving the Munich Agreement on his return to England at Heston Aerodrome. ‘Peace for our time’. Public Domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

24 Nov 202414min

218. Surprised by the man of no suprises

We start this week with Hitler announcing that there would be no more surprises, though we immediately question whether his word could always be wholly trusted. We go on to look at the way Hitler was building a regime which didn’t just want war, above all against what he saw as a Jewish-Bolshevik menace, but actually needed it as the only way to obtain basic products for the German population, and raw materials that the military machine itself had to have. Meanwhile, British foreign policy was under new management, with Anthony Eden as Foreign Secretary in place of the disgraced Samuel Hoare. The Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, told him he wanted better relations with Germany and when Eden asked how he was to obtain them, he told him that it was Eden’s job to work that out. But then Baldwin stood down, and his successor, Neville Chamberlain, had a different approach. He wanted to run foreign affairs himself, and he was intent on going flat out for appeasement. That finally brought the Prime Minister and his Foreign Secretary into a head-on clash, over concessions to Italy, in the hope of securing Mussolini’s assistance. Chamberlain was prepared to recognise that Italy had the right to invade and occupy Abyssinia (Ethiopia today), even though that was a breach of international law. Eden was in favour of appeasement, but not at the cost of unreasonable concessions, and this one he decided really wasn’t reasonable. Eden went. His replacement was Lord Halifax. He’d recently been on a hunting trip to Germany as the guest of Hermann Goering, and came back convinced that the Nazi leaders were reasonable men with whom a sensible set of arrangements could be negotiated. Then Hitler showed that the age of surprises really wasn’t over. He sent troops over the border into neighbouring Austria, to absorb it into the German Reich. There was no resistance in the country, and none from outside either, including from Britain. European great powers didn’t greatly rate the rights of Africa’s native peoples. Writing off the rights of the Abyssinians therefore was no great shock. But this was Austria, a European country, and Hitler invaded and annexed it without the slightest attempt to stop him from abroad. It seemed that appeasers were prepared to step across some red lines in their bid to buy peace through concessions to dictators. Illustration: Members of the Nazi organisation, the League of German Girls, celebrating the arrival of German troops in Vienna. Dokumentationsarchiv des Oesterreichischen Widerstandes Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

17 Nov 202414min

217. An event-packed year (2)

We’re still looking at 1936, a year packed with so many events that it’s taken two episodes to review the main ones. This week, on the domestic, British front: - The year of three kings, as one died, another abdicated for love, and the third took the throne - The Battle of Cable Street where 100,000-300,000 or more counter demonstrators turned out to stop the British Union of Fascists marching through Jewish districts of East London - The Jarrow March and Ellen Wilkinson, the fiery MP for the constituency, and the campaign to tackle the problems of poverty and unemployment in the world’s greatest enpire And in foreign affairs: • Hitler makes clear that whatever’s wrong, it’s down to the Jews • Then silences anti-Semitism and general oppression for a while, to make a success of the Berlin Olympics, spoiled only by an outstanding black athlete from the US • Despite the attempts of the British government, backed by Churchill, to curry favour with Mussolini, he signs the Axis agreement with Hitler • Labour’s policy on rearmament and on the Spanish Civil War remains incoherent and badly in need of revision. Plus from the left of Labour comes an extraordinary call for defeatism in front of Nazi Germany Lots of exciting stuff, then. And it wraps up the year so we can move on next week. Illustration: Ellen Cicely Wilkinson leading the Jarrow Marchers, Fox Photos Ltd, 31 October 1936. National Portrait Gallery x88278 Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

10 Nov 202414min

216. An event-packed year (1)

This episode is our first look at the exciting year of 1936. It was a time when some British politicians tried to appease one dictator, Mussolini, by taking no action to stop invading Abyssinia, in order to have his support against a far worse one, Hitler. As it happens, the effect was only to let Mussolini get away with occupying Abyssinia, leaving the League of Nations even more discredited, and making Britain and France looking pretty foolish. Indeed, that result only encouraged Hitler, who sent troops into the Rhineland which, though German territory, the Treaty of Versailles had demanded should remain demilitarised. It would have been a great moment to block Hitler without fighting a world war, but neither France nor Britain had the will to take military action. Meanwhile, following a military mutiny and uprising, a Civil War had broken out in Spain. The Western powers and the Soviet Union responded with a non-intervention policy, so that all foreign states would stay well out of the war. The reality was that Germany and Italy provided colossal assistance, including military forces, to the Nationalist side of the war, while the Soviet Union provided limited and heavily conditioned assistance to the Republicans. Britain and France kept the pretence of non-intervention, while Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and the Soviet Union were intervening the heck out of the place. In passing, since those three nations were major players in the Second World War in Europe, it strikes me that, just as we should date the start of the war generally to September 1931 rather than September 1939, so we should date the start of the war in Europe to the start of the Spanish Civil War, on 17 July 1936. Meanwhile, in Britain Clement Attlee, new leader of the Labour Party was gradually moving the party towards accepting the need for rearmament. What’s also striking is that, like Churchill, he was looking for some kind of collaboration with the Soviet Union if it came to war with Germany, but even more the United States, which both felt should take the leadership of a Western alliance to defend democracy. Illustration: Italian anti-tank gun at the battle of Guadalajara in the Spanish Civil War. CC BY-SA 3.0 de. Photo by H.G. von Studnitz, from Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-2006-1204-500, Spanien, Schlacht um Guadalajara.jpg Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

3 Nov 202414min