215. A military adventure shakes the kaleidoscope

Britain and France reckoned they’d secured the support of Italy, in the Stresa Front, for their efforts to contain Hitler. Britain was the first to undermine that pleasant understanding, by signing a naval agreement with Nazi Germany on its own. Even so, the British government did what it could to keep Mussolini’s Italy in the Front, a position shared by Winston Churchill. He was already ringing alarm bells over Germany but, proving how difficult prediction can be, he got Italy (and indeed Japan) completely wrong. Then Mussolini showed his true colours by preparing to launch an invasion of Abyssinia, which is now Ethiopia, to extend Italy’s imperial holdings in Africa. Doing so meant spitting in the face of the League of Nations, even though Italy was a member. But Mussolini could do that with impunity. The League, only as powerful as its members, and above all its great power members, Britain and France, allowed it to be, took no effective action against it. In the face of that spinelessness, Mussolini went ahead with his invasion. That had a surprising impact on the Labour Party, whose annual conference started the day after news of the Italian invasion arrived in Britain. Labour decided that it had no further patience with its declared pacifist leader, George Lansbury. He resigned and the jostling started to pick a successor. Clement Attlee, who’d been Lansbury’s deputy, was given the job on a temporary basis, as Britain went into the 1935 general election. It was a huge win for the Tories but Labour also did well, winning nearly three times as many seats as in 1931. Attlee who’d led the party into that success was boosted by it. Viewed by many as poorly qualified for the job and short of personality, he saw off others who thought themselves better suited, and to the surprise of many, was confirmed as leader. Illustration: Italian officers consulting maps as they advance into Abyssinian territory. Public domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

27 Okt 202414min

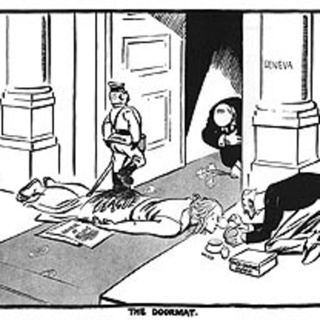

214. The doormat League of Nations

In the mid-1930s, there was still widespread hope across Britain that a major war could be avoided. That could be achieved, many believed, by international negotiation towards disarmament, and by collaboration to enforce the decisions reached. A body existed to achieve just that: the League of Nations. It called a major conference, chaired by Arthur Henderson, former British Foreign Secretary, former leader of the Labour Party. It set out with plenty of great intentions but achieved nothing. Too few countries were prepared to trust others enough to make the cuts in their armaments that might have made a real difference. Meanwhile, another British politician, this time a Conservative, Lord Robert Cecil, one of the architects of the League of Nations and president of the British association dedicated to supporting it, the League of Nations Union, was campaigning for international collaboration to give real force to decisions of the League or elsewhere, so that breaches could be genuinely and effectively punished. He organised an unofficial referendum in Britain, the Peace Ballot, completed in 1935, that showed how massively the British people supported efforts for peace. Sadly, though, that year, 1935, would be the peak of such efforts. Thereafter events would drive the world increasingly towards another war. Indeed, one of those events had already happened, as early as in September 1931: the Japanese invasion of the Chinese territory of Manchuria. Someone like the outstanding political cartoonist David Low would go so far as to identify that moment as the true start of the Second World War. That notion, with which this episode starts, rather suggests that efforts to prevent the Second World War reached their peak, only to fall away afterwards, when it could be argued that, actually, it had already started. Illustration: The Doormat, cartoon of 1933, by David Low. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

20 Okt 202414min

213. Carson honoured, Churchill mocked

We start this episode with the unveiling of the statue of Edward Carson at Stormont Castle in Northern Ireland. It rather makes the point that a man who helped organise an armed force against British law, and even to call on British soldiers to mutiny rather than fire on rebels – no doubt because to him and his friend they were the right kind of rebels – could get away with such behaviour if he had the backing of the right circles of power back in England. Not just get away with it, in fact, but be honoured with a statue. From there, we move to India where a man like Gandhi kept finding himself being gaoled by the British authorities for actions far less noxious than Carson’s. A brown-skinned Hindu simply couldn’t be allowed to call on action against the rule of the British government, even if that action was far less subversive of the law than what the white-skinned Protestant Carson had championed. As it happens, the National government in Britain was beginning to consider the possibility of granting a little more autonomy to India, though nothing like as much as enjoyed by white-ruled holdings, such as Australia or Canada, which enjoyed Dominion Status, giving them almost independence. That was far too little for Gandhi, or for Clement Attlee and his Labour Party. On the other hand, it was far too much for Winston Churchill. He fought the government all the way to the point, by the end, of becoming something of a figure of fun in the House of Commons. No one proved that better than his chief tormentor, Leo Amery, despite being a fellow Conservative and a contemporary of his at Harrow school. He used mockery against him in a way that Churchill himself might have been proud of had he used it himself. But the real danger for Churchill was that he was perilously close to becoming a bore. Illustration: the Carson statue outside the home of the Northern Ireland Assembly, Stormont Castle, outside Belfast. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

13 Okt 202414min

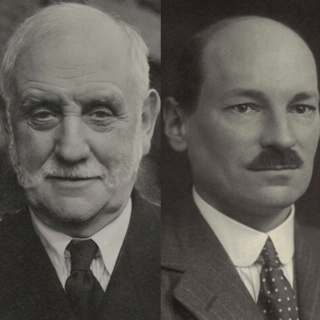

212. Labour struggling, Tories soaring, the economy wobbling

It was a terrible time for Labour, down to just 52 MPs and having to choose a new leadership from a narrow pool from which most of the brightest lights, in the view of many but above all their own, were excluded. The Tories were on top of the world, with a clear majority. MacDonald still led the the National government, but in complete dependence on the Conservatives for his survival in office. A sharp change in direction of economic policy ended the linkage to the gold standard and introduced tariffs on imports. Both initiatives started to improve things, with growth back and with some strength. But the poor remained desperately poor. Illustration: composite of the Labour Party leader, George Lansbury, and deputy leader, Clement Attlee, chosen by default because the obvious candidates weren’t available. Both photos from the National Portrait Gallery: Attlee by Walter Stoneman, 1930, NPG x163783; Lansbury by Howard Coster, 1930s, NPG Ax136093 Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

6 Okt 202414min

211. Troubled times: India, Press Harlots, and Winston Churchill

This episode looks at the impact in Britain of continuing trouble in India. There Gandhi had launched his salt march, walking to the sea to make salt, in breach of the British monopoly and the heavy tax on salt inflicted by the colonial authorities. That had led to his being gaoled. In Britain, the report of the Simon Commission recommended limited reform in India, but not the granting of Dominion Status. That was in spite of the view of one of the Commission’s co-chairs, Labour’s Clement Attlee, who had been convinced of the need for that status following his travels with the Commission around India. The Prime Minister called a Round Table conference in London which had representation from many Indian groups, unlike the Simon Commission which had had none. Unfortunately, the gaoled Gandhi’s organisation, the Indian National naturally didn’t attend, and it was the most significant in the sub-Continent. That rather underlines how silly it is to label an opponent as criminal and then proclaim that you don’t talk to criminals – it makes negotiations meaningless. Fortunately, the Viceroy of India Lord Irwin (later Lord Halifax) released Gandhi and agreed the Gandhi-Irwin pact with him, which included his attendance at a second Round Table. Winston Churchill was furious that any moves were being made towards Indian self-rule at all, and that his party leader Stanley Baldwin backed them. Baldwin was also under pressure from a campaign by press barons to make him adopt a policy backing tariffs on imports. Baldwin saw off that pressure, denouncing the newspaper proprietors for pursing power without responsibility, ‘the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages’. Even so, he began to soften his own opposition to tariffs, further adding to Churchill’s disquiet. By January 1931, he’d had enough and resigned from Baldwin’s leadership team. That, for him, was the start of what he would later call his ‘wilderness years’. Illustration: Gandhi, for Churchill a seditious, half-naked fakir, visiting millworkers in Lancashire while in England for the Second Round Table conference. Photo by Keystone Press Agency Ltd. National Portrait Gallery x137614. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

29 Sep 202414min

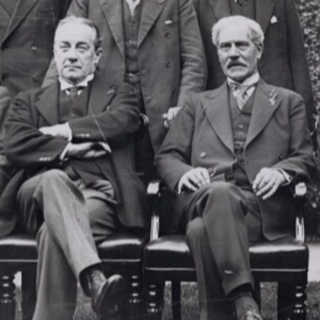

210. Ramsay MacDonald and the coalition that split Labour

The ‘flapper election’ took place on 30 May 1929. The reference was top ‘flappers’, fashionable and slightly shocking young women of the 1920s, who could vote in it because, at last, universal suffrage had been introduced for all adults of 21 or over irrespective of sex or property. The Tories, who’d made some moves, perhaps rather more modest than many might have hoped, towards alleviating property and had been responsible for the reform that gave the flappers the vote, might have hoped to be returned to office in gratitude. They weren’t. Instead, Labour, the biggest single party but again short of a majority, formed a second government under Ramsay MacDonald. As before, and like the Baldwin government that preceded it, it tried to cut public spending. The economy remained stuck in the doldrums and then, after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, it tanked. Workless numbers soared. In 1931, MacDonald decided that the only way to keep reducing spending was to cut unemployment benefit. That was unacceptable to the majority of Labour. The party split over the issue, a split confirmed when MacDonald accepted the king’s plea to stay on as Prime Minister but at the head of a ‘National Government’ including ministers from all three the main parties, Conservative, Labour and Liberal. It in turn went to the country, as the National Government, seeking a ‘doctor’s mandate’ to cure the nation’s ills, on 27 October 1931. The results were spectacular: the National Government was returned to power with a colossal majority, 554 seats out of the total of 615 in the House of Commons. They were disastrous for official Labour, to a rump of just 52 seats. But the picture wasn’t particularly encouraging for MacDonald either. He headed a group with an unassailable majority. However, among the government’s MPs, 470 – a majority of the Commons on its own – were Conservative. His own so-called National Labour group only had 13. He was in office all right. But he was also trapped. He could do nothing without the support of the overwhelming Tory majority. Illustration: Ramsay MacDonald, the Prime Minister, (right), in a detail from a 1931 photo of the National Government cabinet by Press Associations Photos, with Stanley Baldwin (left), the Tory leader whose clear Commons majority of his own made him the real power behind MacDonald’s throne. National Portrait Gallery, x184174. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

22 Sep 202414min

209. Aftermath of defeat

We pick up the story just after the defeat of the 1926 British General Strike. It was a bad time for the unions, with strikes accounting for only just over a fifth as many working days lost in the whole of the next ten years as they had in the single year of 1926. Meanwhile, the Labour Party seemed to be cosying up to some strange people, specifically Lord Londonderry, Tory and coal mine owner, who became a close friend of the Labour leader Ramsay MacDonald. It was also a bad time for the progressive movement, with the Baldwin government bringing in some fairly oppressive legislation, especially against unions and the Labour Party. There were, however, exceptions, in particular the introduction of universal suffrage for all adults (21 years and over) irrespective of sex (oddly enough brought in by a particularly tough Home Secretary, ‘Jix’ (William-Joynson Hix). Neville Chamberlain also brought in some new social legislation, reducing the retirement age for contributory pensions and extending benefits to widows and children of workers who died. The effect was small but welcome. This was also the time when Churchill was riding high and increasingly in rivalry with that same Chamberlain, as they positioned themselves as potential successors to Baldwin for when he eventually retired. What Churchill didn’t seem to realise, however, was that though he’d won most Tories round to his return to their party, too few of them trusted him enough to accept him as leader . The heir apparent, he would discover, wasn’t him, it was Chamberlain. Illustration: Jix (William-Joynson Hix) who brought in universal suffrage despite being a hardline Conservative Home Secretary, leading a dancing group of flappers (young fashionable women enfranchised by the measure), as seen by the cartoonist David Low in a detail of a 1927 cartoon. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

15 Sep 202414min

208. Taking a break

It's time for A History of England to take a short break, until 15 September. So this episode is a brief review of where we’ve got to, after the defeat of the General Strike. That defeat showed the poor in Britain, and workers in particular, that there was little hope of improvement in their conditions through union action alone. Instead political action would be needed, by a government disposed to adopt measures to help them. Which meant progress wasn’t likely to happen soon. That left the majority in Britain in a sorry state, with poor and falling wages combined with high unemployment. Paradoxically, its Empire was at its peak, rather underlining the truth that imperial power didn't necessarily mean prosperity. What's more, even that Empire was under pressure. Decline was already under way, but not everybody had yet recognised the fact. Illustration: A sunset in Ireland (my own photo) Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

18 Aug 20246min