207. Revolution?

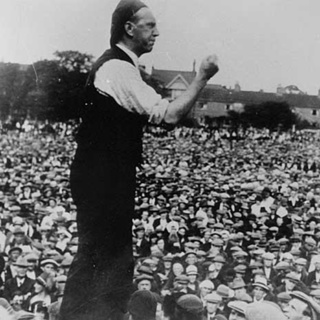

It’s the general strike! This time the unions couldn’t push Stanley Baldwin’s government into making concessions to the miners. That was because while, in his own words, in the previous year Baldwin had not been ready, this time he was. When the miners came out and the TUC with them, they found the government ready to call up volunteers as strike breakers or special constables to support the police. The country had been divided into districts with Civil Commissioners in each of them, ready to ensure essential goods were distributed and order was maintained. In any case, any suggestion that the movement was revolutionary was belied by the moderation the strikers and their leaders showed. That didn’t stop the hardliners in cabinet behaving as though they were facing a major threat to civilisation. Strangely, the leading hardliner was Winston Churchill, even though he was a former Liberal and always keen on alleviating the sufferings of the poor. He edited the government newspaper, the British Gazette, and turned it into a huge-circulation propaganda broadsheet pushing the government line. The BBC, too, broadcasting news for the first time, took a highly pro-government stance. And Churchill wasn't above making shows of military force to underline his propaganda points. The unions weren’t ready for a long strike and their funds began quickly to run out. With legal action threatening against them, and their members suffering, the non-mining unions were looking for a compromise to end the strike. But the miners were at least as intransigent as the mine owners and the government. No compromise was possible. After nine days, the TUC called off the strike. The British Gazette gloatingly proclaimed ‘Surrender!’ The unions had suffered a major defeat. And, once more, the miners were left to fight on alone. Illustration: Arthur Cook, the miners’ leader, addressing a mass meeting of strikers. Public Domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

11 Aug 202414min

206. Confrontation

The Labour government was kicked out of office at the 1924 General Election, in a campaign marked by the Conservative-leaning Daily Mail engaging in some fake news. It published a forged letter claiming to be from the Soviet leader, Zinoviev, suggesting that re-electing Labour would prepare the ground for a Communist takeover. As it happens, Labour’s popular vote went up by a million. But Tory votes were spread much more efficiently across constituencies, so they emerged with a solid majority in the Commons, while Labour lost seats. That result seemed to vindicate Baldwin’s decision to call the previous election in 1923: though the Tories lost, because it rejected the notion of tariff protection, it removed the issue from the agenda and the divisions it produced within the Tory party. They therefore went into the 1924 election united and the effect was just what they wanted – a landslide victory. Baldwin’s position was enormously reinforced. The 1924 election was also when Churchill returned to parliament, but no longer as a Liberal. He was back among the Conservatives in all but name, and to the amazement of many, Baldwin gave him what many see as the second most important position in government, that of Chancellor of the Exchequer. In that position, he took Britain back to the gold standard, against his own initial judgement. It was also against the view of Maynard Keynes, who thought it would damage industry, which it indeed did. The result was new unrest, particularly in the coal industry, with mine owners demanding longer hours and lower wages, which the miners were determined to resist. This time, they had solid support from other unions. The government bought a nine-month stay of execution by paying a subsidy to coal to protect wages and conditions but as the period for which the subsidy was paid drew to an end, tensions grew. Both the mine owners and the miners were adamant. It began to look as though a general strike was inevitable. Did that put Britain on the brink of revolution? Illustration: Baldwin, Tory leader and PM, with Churchill, Chancellor of the Exchequer, after re-ratting to the Tories. Public Domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

4 Aug 202414min

205. The Empire at its peak, the country in the pits

In contrast to the last episode, where we saw how dire the state of the British economy was and how close to violent confrontation society was coming, this episode is the one where we find Britain reaching the peak of its imperial grandeur. It seems that power abroad doesn’t necessarily deliver either peace or prosperity at home. Meanwhile, at home, political instability continued. There were two more elections, in 1923 and 1924, making it three in three years. The middle one was brought on by Stanley Baldwin decided he needed to go for tariff protection for British industry, and decided he needed a mandate for it from the electorate, much to the annoyance of many of his colleagues who felt there was no need to jeopardise their comfortable parliamentary majority just because the leader had decided his conscience needed a new election. As it happened, he lost his bet, and ultimately the election resulted in the formation of the first ever Labour government. A minority government, vulnerable to any loss of support in the Commons, but a government all the same. Anyone, however, expecting radical change from it was in for a disappointment. Though, oddly enough, what brought it down was its supposed softness on communism. Illustration: Ramsay MacDonald in court dress. Public Domain. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

28 Juli 202414min

204. Forward to revolution?

The promise of building Britain into a ‘land fit for heroes’ never came close to being kept. Instead inflation undermined wages, unemployment rose, and living conditions, with widespread slum housing, remained dire. When the government handed coal mining, an industry employing over a million men, back to the private sector after having taken direct control during the war, the drive for profitability led to mine owners demanding major wage cuts. The miners struck and called on the Triple Alliance of Dockers, Miners and Railwaymen, the unions in what were by then the main industries, to support them. This episode looks at how that call failed on Black Friday in 1921, and why. It also looks briefly at how a new Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, saw off an attempt by one of the more entitled Lordlings of England, Lord Curzon, to become Prime Minister in his place, and how he found what slum housing was really like. Illustration: Striking coal miners in Neath, South Wales. Photo: Illustrated London News, 16 April 1921 Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

21 Juli 202414min

203. Carthaginian Peace

Before moving on from the times when Lloyd George held power, we take a look in this episode at one of the major moments of his time as an international statesman: the Paris Peace Conference and, above all, the specific agreement that emerged from it concerning Germany, the Treaty of Versailles. The episode draws heavily on the views of Maynard Keynes on the Treaty and its likely effects, in particular on its failure to react to the massive gap between the expectations of money from Germany by the victors and the real ability of Germany to pay. At the end, we look at the fact that as well as leaving a deep resentment in Germany of the victorious powers, it also left two nations that were actually with them, Japan and Italy, bitter with the outcome of the Paris conference. Germany, Italy and Japan. Compare that list with the membership of the Axis that the Allies would have to fight in World War 2 twenty years after the end of World War 1. An event which Keynes foresaw. Illustration: Covert og John Maynard Keynes’s book, The Economic Consequences of the Peace, of 1919. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

14 Juli 202414min

202. Fall following the decline

The Chanak crisis of 1922 brought Britain to the brink of war with Turkey. Saner heads, in particular those of both the British general on the spot and the Turkish leader, Mustafa Kemal, soon to be Turkish president as Kemal Atatürk, defused the crisis and averted war. But Lloyd George’s handling of the crisis, in which he took a distinctly hawkish stance, added further to the growing dissatisfaction with him as Prime Minister, and with his Coalition government, among rank and file Conservatives. That came to a head in the Carlton Club meeting in October, which voted for the Conservative Party to contest the forthcoming general election as a separate organisation and not merely a component of a Coalition. Both anti- and pro-Coalition ministers felt they had to resign from the government. The pro-Coalition Austen Chamberlain even gave up the leadership of the Conservative Party. Lloyd George, realising that his government was no longer viable, resigned. In the subsequent election, the Tories won themselves a strong working majority. The outcome for the Liberals was disastrous: they were overtaken by Labour which became the official opposition. Never since have the Liberals formed another government of their own, at best being a minor partner in someone else’s. Bonar Law, who had returned to the leadership of the Tories, became Prime Minister. That didn’t last long: cancer finished him within a few months, at which point he was succeeded by a Conservative who’d played a leading role in ending the Coalition, Stanley Baldwin. He and Ramsay MacDonald who had, in the meantime, again won the leadership of Labour, would dominate British politics into the mid 1930s in their rivalry and, sometimes, their collaboration. Illustration: Kemal Atatürk, who led the Turkish forces fighting for the independence of his country, inspecting troops in June 1922. Public Domain Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

7 Juli 202414min

201. Decline before the fall

In 1921 and 1922, the sharks were beginning to circle around Lloyd George. While he thought that getting a Peace Treaty for Ireland was a major success, many felt dissatisfied with a compromise that gave no one entirely what they wanted, and therefore had a sense of being betrayed. That sense deepened as violence continued to surge in Ireland, even leading to the murder by anti-Treaty forces of one of the great figures of Sinn Fein, the pro-Treaty political and military leader, Michael Collins. He’d recorded in his diary, after accepting the Treaty in the negotiations with Britain, that he’d signed his death warrant. So it proved. The Irish violence even spilled over into a high-profile murder in Britain, for which the government’s Irish policies were blamed. On top of that came a scandal over the Lloyd George was shamelessly selling titles of nobility to get himself a political war chest. What he was doing wasn’t illegal at the time, and since he had no party behind him to raise money or run campaigns, he chose this short cut to financing his political work. That, however, did him no favour among Conservatives becoming increasingly disenchanted with him and wondering why, with a majority of their own in the House of Commons, they still had to rally behind a Liberal as Prime Minister. Wasn’t it time to break with him and with his coalition and prepare to form a government of their own again? Top Tories holding positions in his government remained true to the coalition and to him. But their rank and file was running out of patience. And that spelled nothing good for Lloyd George. Illustration: Michael Collins addressing a crowd on St Patrick’s Day, 1922, less than half a year before his death. Public domain photo Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License.

30 Juni 202414min

200. Ireland partitioned

Would Britain go to war in Ireland? Was military action its only available response to the republican party, Sinn Fein, and its determination to govern an independent nation from its own parliament, the Dáil? And, indeed, was it in Britain’s power to go for that option? At first, that certainly seemed to be the way things were heading. Attacks by IRA units against the police or army led to increasingly brutal reprisals by the British authorities, using the notorious Black and Tans or the Auxies, as well as soldiers. Two of the most shocking events were the firing on the crowd at a Gaelic Football stadium on ‘Bloody Sunday’, 21 November 1920, and the burning of Cork the following month. In the end though, the Lloyd Government had to decide that it lacked either the strength or the stomach to force the Irish to bow to their rule. The earlier decision never to negotiate with terrorists had to be dropped and, in the summer and autumn of 1921, discussions finally led to what Lloyd George believed was a triumph of his negotiating skills. He won the agreement of leading Sinn Fein men to a Peace Treaty that partitioned Ireland, hiving off the six Protestant-majority counties of the North which would remain inside the United Kingdom, while the other 26 would form a new Dominion, the Irish Free State, within the British Empire. It seemed like a triumph for him. But that feeling wasn’t going to last long. Illustration: Workers clearing rubble on St Patrick's Street in Cork after the fires (detail). National Library of Ireland on The Commons @Flickr Commons Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License.

23 Juni 202414min