251. Unlucky Jim

In 1976, Jim Callaghan took over from Harold Wilson as leader of the Labour Party and British Prime Minister. He was a competent politician, though not an outstanding one. He did his job well, but he was far from up to taking on an adversary as forceful as the leader of the Conservative Party, Maggie Thatcher.Callaghan’s was the last government of the post-war consensus, based on a belief in a generalised social democracy, seeking to provide the social services needed to ensure that everyone could count on a safety net when one was needed, and built on a foundation of Keynesian economics. Thatcher rejected both social democracy and Keynesianism, which she held responsible for the decline of Britain, militarily, economically and even morally. Her objective was to end the postwar consensus and look for a radically new type of politics (and economics).The other huge innovation she oversaw was an entirely new approach to communication in politics. Using a remarkably talented advertising agency, Saatchi and Saatchi, she and the Conservative party ran devastating campaigns against her opponents. The most famous was focused on a poster of a queue of people in front of a banner marked ‘Unemployment Office’ and with the legend ‘Labour isn’t working’.As well as her powerful and effective campaigning, Labour was brought low by a series of errors made by Callaghan, many of which played into her hands. It was just possible that he might have won an election in 1978, or at least done less badly, but he lacked the foresight to call it (a mistake he later acknowledged). That meant that he went through the season of strikes that came to be known as the ‘Winter of Discontent’ and, instead of choosing the timing of the election himself, was forced to call one when Thatcher brought in a no confidence motion in the Commons, carried by just one vote.The subsequent election, on 3 May 1979, saw the Conservatives win a solid majority of 43. Margaret Thatcher became Britain’s first woman Prime Minister. And, as we’ll start to see next week, launched herself on a programme of radical change.Illustration: Rubbish piling up in the streets as a result of the municipal workers' strike of the during the 'Winter of Discontent'. Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

13 Jul 14min

250. Return of the crisis man

When Harold Wilson formed his second government, he immediately faced a major crisis inherited from Heath’s administration: the coalminers were on strike, a state of Emergency (Heath’s fifth in four years) was in place and Britain was on a three-day week. That gave Wilson some quick wins as he dealt with all three.Other things proved less straightforward. Heath had brought in a power-sharing arrangement in Northern Ireland, under the so-called Sunningdale Agreement, between the Protestant and Catholic communities. Soon after Labour came back to power, however, a strike by Protestant organisations brought the Sunningdale Agreement to an ignominious end.Wilson also came under sustained press attack over scandals in which he seems to have played no reprehensible role (though his cleverness and deviousness did tend to leave him open to accusations of not being entirely straight).He also had to deal with his pledge to renegotiate the terms on which Britain had joined the Common Market. The renegotations achieved little but their real aim was simply to be seen to have been undertaken before the referendum was held. The process, however, left Wilson more convinced than ever that Britain had to stay in. That lost him support on the left of Labour, while the right behaved in ways that left Wilson suspicious of what it was up to.All these pressures became hard to sustain and Wilson, who’d long said he’d go by the time he was sixty, stood down both from the premiership and from the Labour Leadership just a few weeks before reaching that age. That marked the end of an era.Illustration: Ian Paisley addressing a crowd during the Ulster Workers Council Strike against the Sunningdale Agreement. Photo from the Irish News.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

6 Jul 14min

249. Who governs Britain?

How did Heath end up calling an election on the question of who governed the country? Especially as the choice he seemed to be offering was between him and the minders. This episode traces the impact of two major shocks, the ending of Bretton Woods in 1971 and the oil shock of 1973, combined with the inflation that followed a last Tory attempt to manufacture a boom from Keynesian economics, that drove Heath to that decision. It also shows how all this led to the unravelling of the postwar consensus, particularly on economic policy, and the emergence of a new, radical current in the Conservative Party seeking to replace the consensus by a new departure in economic thinking.When Heath, having lost the February 1974 election, lost the next one, in October, too, the pressure against him became irresistible. He called a leadership election for early 1975. The self-destruction of the campaign of the initial darling of the right, Sir Keith Joseph, opened the door to the first possible ascent to leadership of a major British party by a woman. The brilliant election tactics of Airey Neave, ex-intelligence operative, ensured that she achieved it.Illustration: A Tory leader and his successor: Ted Heath and Margaret Thatcher. Photo from the Guardian, PA Archive/Press AssociationMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

5 Jul 14min

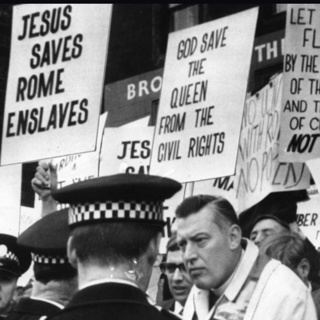

248. Withered Heath

Ted Heath’s government had to deal with two problems drawn from Britain’s postimperial standing: • adapting to its loss of global status, by negotiating, at the third time of asking and for the first time successfully, Britain’s entry to the European Economic Community, which happened on 1 January 1973• dealing with a hangover from the imperial past, as violence surged in Northern Ireland, addressed by direct rule of the province from London, internment without trail and with violent action by British troops, including some massacres, culminating in Bloody Sunday in Derry/Londonderry (‘Stroke City’) on 30 January 1972. As well as being significantly bloodier, Health's way of dealing with Northern Ireland proved far less successful than his negotiations with European partners.This episode ends with Heath’s attempts to solve economic problems and with the double confrontation he had with the miners. The second of these would cause him to pose the very question of who ruled the country. The answer from voters was going to disappoint him.Illustration: Ian Paisley, the outspoken Protestant Ulsterman, campaigning against Catholicism (‘Jesus Saves, Rome Enslaves’). Detail from a photo in Covert History, https://coverthistory.ie/2024/04/06/bombs-spooks-and-child-abuse-the-sordid-secret-history-of-the-dup/.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

22 Jun 14min

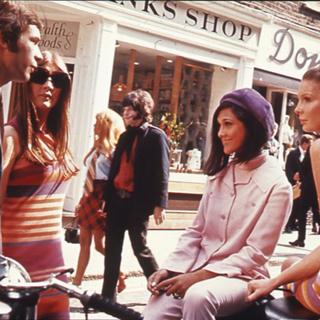

246. The sixties, swinging - high and low

According to the English poet Philip Larkin, the sixties saw the invention of sexual intercourse. While that may not be quite the case, it was certainly a time when a lot of people decided that it was time to revolutionise the way society dealt with sex. The Wilson government saw in a lot of reforms in this direction.There was a partial decriminalisation of gay sex. Abortion was legalised. Divorce was made easier.And there were reforms too in other fields, such as the abolition of the death penalty for murder, the first steps to make racial discrimination illegal, and an explosion in educational opportunity, above all in higher education.But there were plenty of bleak moments too. The Aberfan disaster in Wales was an appalling tragedy. Nor was the economy doing anything like as well as Wilson might have liked. Indeed, after resisting devaluation in 1964 and 1966, he finally had to give way in 1967, cutting the value of sterling by just over 14%.That would be used against him. He’d fallen out with the press and devaluing after saying he wouldn’t gave it a cause on which to attack. Especially when he said that the ‘pound in your pocket’ hadn’t been devalued. Oh, boy, that would be used against him.The end of the sixties wasn’t looking too good for him.Illustration: The Swinging Sixties: Carnaby Street, London. From the National Archives, UKMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

8 Jun 14min

245. Pressures preventing progress

The Wilson government got off to a pretty sticky start, with the new Prime Minister learning, more or less as he arrived at Downing Street in October 1964, that the trade deficit for the year was likely to be twice as bad as he’d expected. One option to deal with the problem was devaluation, but that Wilson ruled out: he remembered how it had been when the Attlee government had devalued, and he didn’t want to face that loss of national prestige or the resentment devaluation had produced, all over again. The problem was that sticking with the pound at an artificially high value meant costs for government which killed many other ambitions, in particular introducing an element of planning and using it to generate growth.Still, the US was pleased Britain hadn’t devalued. It was, however, less pleased that Britain wasn’t sending troops to join its war in Vietnam, but that was a red line for Wilson. He didn’t like wars and he wasn’t inclined to send young British people into harm’s way for a war whose moral grounds many were now questioning and which it wasn’t obvious the US could even win.And Wilson also had to face another grisly chapter in the collapse of empire, when Southern Rhodesia, renamed Rhodesia and under a government headed by the hardline Ian Smith, went for a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI). Again, Wilson however much he disliked seeing Rhodesia hanging on to white rule ignoring its black majority, wasn’t prepared to go to war over the issue. Instead, he tried to use sanctions to bring Smith to his knees, a well-intentioned tactic which simply didn’t work.Illustration: The funeral cortège of Winston Churchill winding its way through London. Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

1 Jun 14min

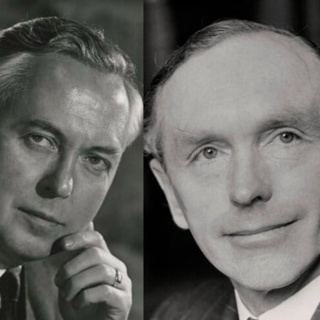

244. Harold gets Home

Here we’re focusing on the changes that took place in Britain after Supermac (Harold Macmillan) stood down as Prime Minister.A lot of how that went depended on the Opposition formed by the Labour Party. Initially it was led by Hugh Gaitskell from the right of the party, with Aneurin Bevan giving him a bad time from the left, while a serious threat was growing from Harold Wilson, formerly of the left which he’d deserted, now of the right which wasn’t sure it could trust him. An object of suspicion across most of the parliamentary party, Wilson was nonetheless appreciated for his ability and for his excellent rapport with voters.Then two key figures died. Bevan, the man seen by so many, for so long, as the leader in waiting, died in 1960. Then, in 1962, it was the turn of Gaitskell himself. All of a sudden, the way was clear for Wilson to forge ahead. Though not fully trusted by either wing of the party, both saw him as something of a least bad option – the left felt he at least had roots amongst them, the right that he'd at least worked with Gaitskell. Wilson secured the leadership with exactly as many MPs voting against him and voted for him, winning only because neither of the other two candidates could take more votes than he did.Wilson showed his skill in the last months of Macmillan’s government, giving him a bad time over such matters as the Profumo scandal. Over that row, Wilson played his cards with great intelligence, enhancing his stature while Macmillan lost his credibility and eventually stood down. He was succeeded by Alec Douglas Home (pronounced Hume), cheating RAB Butler of the prize yet again.As a result, both main parties went into the 1964 general election under new leaders. Home gave Wilson a heck of a run for him money, but in the end Labour won though by a painfully small majority in the Commons. So small that Wilson would be under constant threat of being brought down if a small number of his MPs turned against him.It was clear there would have to be another election pretty soon.Illustration: Harold Wilson by Walter Bird, 25 May 1962National Portrait Gallery x45598, and Alec Douglas Home, unknown photographer, circa 1955, National Portrait Gallery x136159Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

25 Mai 14min