267. Bliar

As the title of this episode suggests, this is where we look at how Tony Blair’s reputation was wrecked by the growing awareness that he’d produced infamously bad justifications to launch Britain into war in Iraq. Many people now reversed the vowels in his name, making Blair into Bliar. For a man who’d once assured Britain that he was a ‘straight sort of guy’, being seen as a liar was quite a fall.Despite all that, Blair had racked up quite a series of achievements. This episode looks at some of them, particularly in education and healthcare. He was, however, very much a ‘yes, but’ Prime Minister: many of his achievements were associated with a failure, either immediately or stored up for the future, which rather qualified how admirable they would ultimately appear. So, alongside his achievements, the episode also looks at how often they were accompanied by a ‘but’.That and the terrible legacy of two wars, in Afghanistan and Iraq, were the background of Blair’s campaign for the election of 2005. He took Labour to its third victory in a row in that contest, an unprecedented accomplishment for the party. However, while it left his government with a strong majority, the win fell short of what would qualify as a landslide – he couldn’t pull off Thatcher’s trick of winning three straight landslide victories in a row.What’s more, he was under increasing strain. The shine had come off his government. And Gordon Brown, up till then his Chancellor of the Exchequer, was putting him under pressure to stand aside. After all, Brown had dropped campaign against him for the Labour leadership back in 1994; now it was his turn at the premiership.Two years into his third government, Blair agreed. In May 2017, he stood down. Gordon Brown at last got his chance to show what he could make of the top job. We’ll see how that went next week. Illustration: ‘Bliar’ button produced by the Stop the War Coalition, from the Imperial War Museum, which produced the photo.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

9 Nov 14min

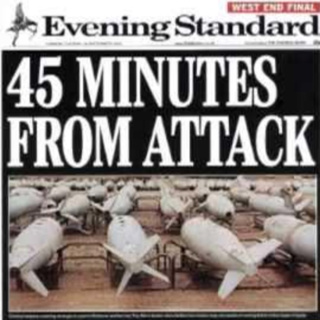

266. A time of dodgy dossiers

When Tony Blair took Britain to war in Iraq in 2003, as part of a US-led and rather limited coalition of nations, it was against the will of large numbers of Brits expressed in possibly the biggest demonstration in British history. He’d also decided to hold a vote in parliament as to whether to go into the war, something he didn’t strictly have to do since it was a so-called ‘prerogative power’, one of the powers inherited from the monarch though exercised, not by the whole of parliament, but by ministers with no need to obtain parliamentary approval. His decision set a new precedent in requiring parliamentary authority to go to war. He also made it a matter of confidence, so his government would have fallen had he lost.That didn’t stop a massive rebellion among Labou MPs, when nearly 40% failed to rally to the government’s support. That didn’t bring him down or prevent involvement in the war, because the Conservatives came to his rescue. It did, though, mean that he took Britain into the conflict in Iraq in the teeth of opposition both from around the country and from many within his own parliamentary party.To push for support, he’d presented parliament with two dossiers detailing the dangers represented by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Both have been shown to be shot through with false claims. That meant that the war was fought on false premises. Such a war, fought on that basis, marked the end of what Blair had once seemed to value, the government’s commitment to an ‘ethical foreign policy’. It’s no surprise that the architect of that policy, Robin Cook, and two other ministers resigned from the government.It also meant that he as well as the victims of the war would be paying a heavy price for having got involved in it. As we’ll discover in the next episode.Illustration: ‘45 mins from attack’: headline in the Evening Standard newspaper, in response to the September 2002 dossier on supposed weapons capabilities in Iraq.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

2 Nov 14min

265. War in a unipolar world

By the latter part of the twentieth century, the world had become unipolar. The Soviet Empire collapsed even more rapidly than the British one had after the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. China was not yet the force it is today. The US was at the pinnacle of its global power.That made it all the more unbearable that it came under assault within its own borders by the terrorists of the 9/11 attack in 2001. A reaction was inevitable. We saw last time how it invaded Afghanistan, but that seemed barely justified since there’s no evidence of Afghan involvement in the attacks. By 2003, the US as ready to turn its military aggression against another nation in what it called its ‘war on terror’, a strange notion of waging war against an abstract noun. Concretely, its new target was Iraq. Sadly, however, Iraqi contact with the 9/11 attacks had proved as difficult to substantiate as Afghanistan’s. But the US put together an international coalition for war there, as it had once before in 1990-91, to throw Iraqi invaders out of Kuwait.This though would be much smaller coalition, with fewer nations prepared to support President George ‘Dubya’ Bush’s new campaign. It didn’t help that it looked suspiciously at least partly aimed at completing the work of his own father, George HW Bush, who’d been president during the previous war on Iraq, by bringing down the dictator Saddam Hussein.One of the nations right alongside the US was Britain. That would leave a lasting mark on Tony Blair’s legacy. Which might as a result not have been quite as glowing as he might have liked.Our subject for next week.Illustration: Government buildings burning in Baghdad following a US airstrike in March 2003. Photo Ramzi Haidar / AFP / Getty from ‘The Atlantic’Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

26 Okt 14min

264. Ethics, votes and wars

We saw in the last episode, that Britain’s involvement in the NATO intervention in Kosovo could be regarded as part of an ‘ethical foreign policy’, since its objective, many felt, was humanitarian, though others disagreed. Another military action, to support the government of Sierra Leone against rebellion, was more clearly humanitarian rather than self-serving, and so easier still to defend on ethical grounds.All this, together with a strong economy and some reforms that were beginning to bear fruit, in the social, educational and health arenas, but Blair’s Labour government in a strong position. So it called a general election in June 2001, when it would set out to do something the party had never achieved before: win a Commons majority, serve out a term in office, and then win another.And Blair pulled it off. Indeed, not only did Labour win, it took another landslide majority.Celebrations didn’t last long though. Within three months of the election win, terrorists attacked the US in the atrocity we now call 9/11. An attack that serious led to a massive response, but not against the nation from which most of the terrorists and their leader, Osama bin Laden, came, which was Saudi Arabia, but against the nation that offered bin Laden refuge, Afghanistan.That rather questioned the extent to which Labour was pursuing a foreign policy that could be called ethical. However, far worse was still to come. That, though, we’ll see in the next episode.Illustration: the Twin Towers ablaze on 9/11, 11 September 2001. Public domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

12 Okt 14min

262. Uncool

In the early years of Blair’s premiership, his supporters liked to refer to Britain as ‘Cool Britannia’, in a play on the title of the song ‘Rule Britannia’. Last week, we talked about some of the cooler things the Blair government did at this time, including the breakthrough in the Northern Irish peace process, specifically the Good Friday Agreement.This week, we look at some of the distinctly uncool aspects of its rule and, funnily enough, we’ll focus for much of the episode on Northern Ireland again. This time, though, we’ll talk about what happened to the person who, perhaps more than any other, made sure the Agreement was reached, Mo Mowlam. And her treatment might well be regarded as far from cool.One of the uncool parts of it was that she was replaced by Peter Mandelson. He’s been in the news again in our time, forced to resign for the third time from a political appointment, this time as ambassador to the US. But the first time he was forced to resign, over a financial scandal which was uncool enough, it was just ten months before he came back into government, taking over from Mowlam, which made it uncooler still.Just as uncool was the Ecclestone scandal, where Blair tried to help out the boss of Formula 1 racing, who’d made a large contribution to the Labour Party. What made that particularly uncool was that Blair denied that he’d made the decision to help Ecclestone very quickly, before handing back his donation, and the truth only came out thanks to a Freedom of Information request. And though he introduced the Freedom of Information Act, he later kicked himself for doing it, which was even more uncool.Plenty that wasn’t cool, then, in Cool Britannia. For the passage on Northern Ireland, and specifically on Mo Mowlam, from the video of Blair's speech to the 1998 Labour Conference, take a look at:https://www.c-span.org/program/international-telecasts/labour-party-conference/118168Illustration: A photo taken shortly before the bomb blast in Omagh. It’s uncertain who the photographer was. The remains of the camera were found in the rubble after the bomb exploded. Image currently displayed by the Irish historian Wesley Johnston on his website: http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/users/ireland/past/omagh/before.htmlMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

28 Sep 14min

261. Cool Britannia

The Blair government threw itself into action as soon as it was formed.Rather confirming the existence of a deal between them, something they’ve never confirmed, Blair quickly appointed Gordon Brown Chancellor. As well as steps, such as making the Bank of England independent and introducing a minimum wage, on which they fully agreed, there’s also evidence that, as suspected, Blair had promised Brown authority of his own, unprecedented for a Chancellor, over social security. Brown focused on families with children and on pensioners, and his reforms did bring in a significant redistribution of wealth, increasing the incomes of the poorest at the expense of the richest. Strangely, however, this led to no reduction in inequality: since the 1980s, the time of Thatcher and Reagan, the pressure towards growing inequality, whose effect we feel strongly today in the power of so-called oligarchs, had been sustained and was apparently irresistible. The Blair government acted to improve gay rights, equalising the age of consent for straight and gay sex, abolishing the notorious Section 28 and introducing civil partnerships for gay couples.It also worked on devolution, with parliaments set up for both Scotland and Wales, with substantial powers though nothing like independence, and a new strategic authority for London, which had been without one since Thatcher abolished the Greater London Council in 1986.When it came to Northern Ireland, there was still a lot of work to do. Referendums in both the Republic and in the North endorsed the Good Friday Agreement, despite far lower enthusiasm among Northern Protestants than among Catholics in the province and citizens of the Republic. Now there was some hard, detailed work to do to implement the agreement. That would include a sad collateral casualty. That, though, is something which we’ll talk about next week.Illustration: Blair and Brown, working in partnership. For now, Photo from 'The New Statesman’.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

21 Sep 14min

260. New Dawn

It was a new dawn. Or at least so Tony Blair said, as he emerged from his landslide victory in the 1997 General Election. It’s what he would say, isn’t it?Still, there was some truth to the claim. It was the end of eighteen years of Conservative rule. Eleven of them had been under the Iron lady, Maggie Thatcher. And whatever her achievements, she had certainly been the most divisive leader since the Second World War, as she made clear by explicitly breaking with the consensus politics that had marked the postwar scene up to her. It was also revealed in the deeply divided reactions to her death in 2013, with tributes from some (including Tony Blair) and celebration (Ding-dong, the witch is dead) from others.She’d been followed by John Major, in a government marked above all by division within his own party, as well as some blunders. Also marked, however, by one big breakthrough: the beginning of a peace process in Northern Ireland which he couldn’t take through to completion, but which got some momentum behind it all the same.That’s the theme the episode concludes with, because it fell to Tony Blair’s government to take that process forward. Its work would lead to the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. That would only be possible thanks to the unflagging support of the governments in both Dublin and London and, indeed, in Washington DC.As well as to the courage and willingness to go out on a limb of an extraordinary woman, the first female Northern Ireland Secretary and someone of outstanding firmness of will combined with willingness to negotiate to anyone she needed to win around. And who was she?Why, she was Mo Mowlam.Illustration: Mo Mowlam. Photograph: Paul McErlane/AP from 'The Guardian'Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

14 Sep 14min