255. Maggie: lioness or poodle?

Maggie Thatcher in 1987 pulled off a trick that had eluded all other British Prime Ministers of the twentieth century: she won three general elections in a row. Even more, she won a second Commons landslide down from the 144 seats in 1983, but still massive at 102 seats. It was a remarkable feat, to set alongside her being the first woman Prime Minister of Britain, though she always preferred to present herself as the first scientist.With that huge majority, she seemed well placed to pursue her policy agenda to make Britain great again. But that’s where she ran into problems. This week, we’re going to talk about what the obstacles to her were in foreign affairs, before turning to the domestic ones next week.She had three main paths to choose between: she could go all in on the Atlantic Alliance with the US, banking on the special relationship; she could go with the Commonwealth, using that association of former imperial possessions to rebuild British global power; or she could throw the country’s lot in with Europe, sacrificing some British sovereignty to the EEC, in return, as Harold Macmillan had written quarter of a century earlier, for sharing in the sovereignty the other nations had given up.The problem was, as experience would show, that the special relationship with the US had become deeply one-sided, with the US treating Britan as very much a junior partner (which, to be fair, it was). While her backers praised her for standing up against those in parliament who resented granting the US permission to fly bombing raids against Libya from British bases, calling her a lioness in a den of Daniels, those opponents regarded her as a poodle doing the bidding of the American president. As for the Commonwealth, this loose association of nations with no real structure for taking or acting on decisions, was never going to get Britain anywhere. And when it came to Europe, Thatcher grew increasingly sceptical about the EEC as time went on, resenting any granting of authority to it outside the purely economic area.That, sadly, left Thatcher with no real option for taking things forward. Majority or not, she was increasingly boxed in. Lioness or poodle, she found her way blocked in every direction.Illustration: 'You lead and I'll follow': Thatcher dancing with Reagan, a special relationship in which the US calls all the shots. Photo by Charles Tasnadi from the Globe and Mail.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

10 Aug 14min

254. Maggie reaching the top

Thatcher’s victories, including a general election landslide and breaking the miners’ strike, emboldened her to launch another phase in the reduction of the role of the state in the British economy. Nationalised industries were privatised, with encouragement given to individuals to buy the shares, which they did with enthusiasm. This came on top of the continuing success of council house sales under the ‘Right to Buy’ scheme. Extending home and share ownership to far more people, from far more modest backgrounds than ever before, Thatcher claimed, was opening an era of popular capitalism.The reality, however, was more nuanced. Many buyers of shares in privatised companies sold them again, taking a quick profit, because the share price on flotation had been low and it climbed dramatically afterwards. Many owners of former social housing also sold their properties, leading to a large minority ending back again as rentals, but with private landlords not bound by the policy of affordable rents that councils had applied.Similarly, another great initiative of the Thatcher government, the deregulation of the London Stock Exchange, seemed to go brilliantly. London regained its status as a major financial centre. It would only be twenty or so years later that some of the downside emerged, when the encouragement to banks to engage in speculation became a contributing factor to the 2008 crash.The IRA was running a terrorist campaign in Britain too, one that nearly claimed Thatcher's own life, when a bomb was planted in Brighton’s Grand Hotel, where she and many leading Tories were staying for the party conference. Thatcher reacted with commendable courage and resolution at the time, and later even went so far to negotiate an Anglo-Irish agreement, again giving the Republic a consultative role in the affairs of Northern Ireland. It didn't go far enough, as the Good Friday agreement would a decade later, but it was an important step,And then there was the Westland affair, when a British helicopter manufacturer ran into difficulties, and a dispute broke out in cabinet over which two options, American or European, to back for a rescue. Ultimately, that led to the Minister of Defence, Michael Heseltine, openly defying Thatcher. That was an ominous event, a first crack in the previously apparently indestructible fortress of support for Thatcher among her colleagues.It was a foretaste of unpleasantness ahead but for the moment that was still quite a way in the future.Illustration: Margaret Thatcher in defiant mood, speaking out against terrorism at the 1984 Conservative Party conference, after the bomb attack on the Grand Hotel in Brighton. Photo from The Guardian. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

3 Aug 14min

253. The Enemy Within

What had converted Maggie Thatcher from something of a lame duck into a front runner for the next British general election?While the economy had begun to pick up, that had been patchy at best, with some parts of Britain suffering badly while the general picture was improving. That’s what made me feel then, and leaves me feeling now, that it was the victory in the Falklands that made her more or less unassailable, far more than any economic achievements.The election, when it came, gave her a landslide majority in the Commons, making her the only British Prime Minister in the twentieth century to have improved her majority at her second election. But that disguises the fact that her popular vote actually fell slightly, mostly down to the impact of the SDP-Liberal Alliance, taking far more votes than the Liberals alone at the previous election. That won them a disappointing number of MPs, because of the perversity of the first past the post system, while giving her a huge victory, down to the exactly the same thing.Next, having defeated an enemy without, the Argentinians, she took on what she regarded as a more serious threat, the enemy within. That was the trade union movement and more particularly the miners. When they struck against mine closures, her smart work preparing the ground for resisting even a long strike, combined with the incompetence of a radical but inept leader of the miners’ union, Arthur Scargill, she was able to crush the strikers. A second victory in three years. But not against an external enemy. This was against the enemy within, a once proud and powerful working-class movement, now reduced to impotence.Illustration: A scene from the Battle of Orgreave between mineworker pickets and police. Photo from the Doncaster Free Press. Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

27 Juli 14min

252. Iron Lady

Mrs Thatcher’s first term in office was one of the great get out of jail events. She came into office intent on braking with the Keynesianism and social democracy of the postwar consensus. She drew on the ideas of the economists Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman (both briefly discussed in this episode), with their championing of the free-market and, in Friedman’s case, of monetarism. Initially, however, things didn’t go well: unemployment soared, the economy shrank and even inflation, the very issue monetarism set out to tackle shot up. She maintained, however, that she had no intention of changing tack, declaring ‘the lady’s not for turning’. By 1981, she was sitting on the worst favourability ratings of any Prime Minister since records had been kept.But then the economy started to come back from recession, helped by the fact that oil began to flow from Britain’s North Sea fields, inflation fell, and her ‘right-to-buy’ scheme allowing tenants of council housing to buy their homes proved popular. Nothing, though, helped her as much as the behaviour of two enemies.Labour kept up its drift leftwards leading to its split, with the Social Democratic Party launched by some senior figures leaving the party, most notably Roy Jenkins. In alliance with the Liberals, they represented a dangerous splitting of the anti-Tory vote.Even more helpful for Thatcher, was the invasion of the Falkland Islands – or Islas Malvinas – launched by the Argentinian junta under General Galtieri. By responding with military force, and winning, she was able to turn herself into a victorious war leader and a hero to many in Britain. Her approval rating surged to 51%.Suddenly, from someone expected to lose the next general election, she’d become a practically unbeatable leader for it.Illustration: British paratroopers entering Port Stanley – Puerto Argentino – in the Falkland Islands – las Islas Malvinas – at the end of the war against Argentina for their possession. Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

20 Juli 14min

251. Unlucky Jim

In 1976, Jim Callaghan took over from Harold Wilson as leader of the Labour Party and British Prime Minister. He was a competent politician, though not an outstanding one. He did his job well, but he was far from up to taking on an adversary as forceful as the leader of the Conservative Party, Maggie Thatcher.Callaghan’s was the last government of the post-war consensus, based on a belief in a generalised social democracy, seeking to provide the social services needed to ensure that everyone could count on a safety net when one was needed, and built on a foundation of Keynesian economics. Thatcher rejected both social democracy and Keynesianism, which she held responsible for the decline of Britain, militarily, economically and even morally. Her objective was to end the postwar consensus and look for a radically new type of politics (and economics).The other huge innovation she oversaw was an entirely new approach to communication in politics. Using a remarkably talented advertising agency, Saatchi and Saatchi, she and the Conservative party ran devastating campaigns against her opponents. The most famous was focused on a poster of a queue of people in front of a banner marked ‘Unemployment Office’ and with the legend ‘Labour isn’t working’.As well as her powerful and effective campaigning, Labour was brought low by a series of errors made by Callaghan, many of which played into her hands. It was just possible that he might have won an election in 1978, or at least done less badly, but he lacked the foresight to call it (a mistake he later acknowledged). That meant that he went through the season of strikes that came to be known as the ‘Winter of Discontent’ and, instead of choosing the timing of the election himself, was forced to call one when Thatcher brought in a no confidence motion in the Commons, carried by just one vote.The subsequent election, on 3 May 1979, saw the Conservatives win a solid majority of 43. Margaret Thatcher became Britain’s first woman Prime Minister. And, as we’ll start to see next week, launched herself on a programme of radical change.Illustration: Rubbish piling up in the streets as a result of the municipal workers' strike of the during the 'Winter of Discontent'. Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

13 Juli 14min

250. Return of the crisis man

When Harold Wilson formed his second government, he immediately faced a major crisis inherited from Heath’s administration: the coalminers were on strike, a state of Emergency (Heath’s fifth in four years) was in place and Britain was on a three-day week. That gave Wilson some quick wins as he dealt with all three.Other things proved less straightforward. Heath had brought in a power-sharing arrangement in Northern Ireland, under the so-called Sunningdale Agreement, between the Protestant and Catholic communities. Soon after Labour came back to power, however, a strike by Protestant organisations brought the Sunningdale Agreement to an ignominious end.Wilson also came under sustained press attack over scandals in which he seems to have played no reprehensible role (though his cleverness and deviousness did tend to leave him open to accusations of not being entirely straight).He also had to deal with his pledge to renegotiate the terms on which Britain had joined the Common Market. The renegotations achieved little but their real aim was simply to be seen to have been undertaken before the referendum was held. The process, however, left Wilson more convinced than ever that Britain had to stay in. That lost him support on the left of Labour, while the right behaved in ways that left Wilson suspicious of what it was up to.All these pressures became hard to sustain and Wilson, who’d long said he’d go by the time he was sixty, stood down both from the premiership and from the Labour Leadership just a few weeks before reaching that age. That marked the end of an era.Illustration: Ian Paisley addressing a crowd during the Ulster Workers Council Strike against the Sunningdale Agreement. Photo from the Irish News.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

6 Juli 14min

249. Who governs Britain?

How did Heath end up calling an election on the question of who governed the country? Especially as the choice he seemed to be offering was between him and the minders. This episode traces the impact of two major shocks, the ending of Bretton Woods in 1971 and the oil shock of 1973, combined with the inflation that followed a last Tory attempt to manufacture a boom from Keynesian economics, that drove Heath to that decision. It also shows how all this led to the unravelling of the postwar consensus, particularly on economic policy, and the emergence of a new, radical current in the Conservative Party seeking to replace the consensus by a new departure in economic thinking.When Heath, having lost the February 1974 election, lost the next one, in October, too, the pressure against him became irresistible. He called a leadership election for early 1975. The self-destruction of the campaign of the initial darling of the right, Sir Keith Joseph, opened the door to the first possible ascent to leadership of a major British party by a woman. The brilliant election tactics of Airey Neave, ex-intelligence operative, ensured that she achieved it.Illustration: A Tory leader and his successor: Ted Heath and Margaret Thatcher. Photo from the Guardian, PA Archive/Press AssociationMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

5 Juli 14min

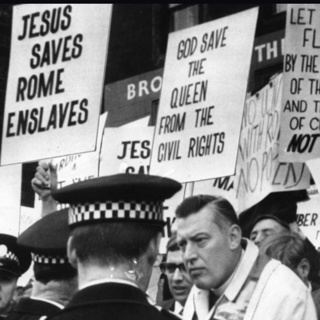

248. Withered Heath

Ted Heath’s government had to deal with two problems drawn from Britain’s postimperial standing: • adapting to its loss of global status, by negotiating, at the third time of asking and for the first time successfully, Britain’s entry to the European Economic Community, which happened on 1 January 1973• dealing with a hangover from the imperial past, as violence surged in Northern Ireland, addressed by direct rule of the province from London, internment without trail and with violent action by British troops, including some massacres, culminating in Bloody Sunday in Derry/Londonderry (‘Stroke City’) on 30 January 1972. As well as being significantly bloodier, Health's way of dealing with Northern Ireland proved far less successful than his negotiations with European partners.This episode ends with Heath’s attempts to solve economic problems and with the double confrontation he had with the miners. The second of these would cause him to pose the very question of who ruled the country. The answer from voters was going to disappoint him.Illustration: Ian Paisley, the outspoken Protestant Ulsterman, campaigning against Catholicism (‘Jesus Saves, Rome Enslaves’). Detail from a photo in Covert History, https://coverthistory.ie/2024/04/06/bombs-spooks-and-child-abuse-the-sordid-secret-history-of-the-dup/.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

22 Juni 14min