247. Hopes dashed

After talking last week about his government’s achievements in the social sphere, this episode looks at the difficulties Wilson faced in economics and foreign affairs.One way Wilson explored to address economic problems was to make a second application for Britain’s entry to the Common market, then called the European Economic Community and now the European Union. However, like Macmillan before him, he ran into the immovable obstacle of de Gaulle, despite believing like Trump that he could overcome opposition by personal conversation with political leaders.He had the same disappointment in personal negotiations twice more. Once waswith the Rhodesian Prime Minister, Ian Smith, the second in his offer to mediate over the Vietnam War between US President Johnson and the Soviet Premier Kosygin.He did have some success, though it attracted him more ridicule than admiration, in the military intervention he authorised on the tiny Caribbean island of Anguilla and which came to be mocked as ‘the Bay of Piglets’.On the domestic front he’d long balanced the leadership ambitions of Jim Callaghan against those of George Brown. After Brown’s departure, he did the same with Callaghan and Roy Jenkins. His hold on office came under threat as his public credibility sank. The threat intensified following the controversy over the proposals to control union activity through the courts, outlined in the paper ‘In Place of Strife’. Surprisingly advanced by a leftwinger, Barbara Castle, and backed by Wilson, it seemed to fly in the face of the rationale of Labour’s very existence, founded as it had been to defend the unions.Eventually the proposals were dropped. Then with better economic news Labour began to climb in the polls. Encouraged, Wilson called a general election in June 1970. But it turned out that any optimism generated by the opinion pollsters was illusory.Ted Heath’s Conservatives won the election and formed a new government.Incidentally, the German translation of the podcast has now moved past the Tudors and is now dealing with the Stuarts. It’s available at:https://open.spotify.com/show/08M357CvtiWJsnEGyxitco?si=64613c2919df4a27Illustration: the kind of military action we can all appreciate. British forces restoring order in Anguilla in the 1969 ‘Bay of Piglets’ operation (from Anguilla Police Unit 1969... By: Taff Bowen (AKA "Dickiebo"))Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

15 Juni 14min

246. The sixties, swinging - high and low

According to the English poet Philip Larkin, the sixties saw the invention of sexual intercourse. While that may not be quite the case, it was certainly a time when a lot of people decided that it was time to revolutionise the way society dealt with sex. The Wilson government saw in a lot of reforms in this direction.There was a partial decriminalisation of gay sex. Abortion was legalised. Divorce was made easier.And there were reforms too in other fields, such as the abolition of the death penalty for murder, the first steps to make racial discrimination illegal, and an explosion in educational opportunity, above all in higher education.But there were plenty of bleak moments too. The Aberfan disaster in Wales was an appalling tragedy. Nor was the economy doing anything like as well as Wilson might have liked. Indeed, after resisting devaluation in 1964 and 1966, he finally had to give way in 1967, cutting the value of sterling by just over 14%.That would be used against him. He’d fallen out with the press and devaluing after saying he wouldn’t gave it a cause on which to attack. Especially when he said that the ‘pound in your pocket’ hadn’t been devalued. Oh, boy, that would be used against him.The end of the sixties wasn’t looking too good for him.Illustration: The Swinging Sixties: Carnaby Street, London. From the National Archives, UKMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

8 Juni 14min

245. Pressures preventing progress

The Wilson government got off to a pretty sticky start, with the new Prime Minister learning, more or less as he arrived at Downing Street in October 1964, that the trade deficit for the year was likely to be twice as bad as he’d expected. One option to deal with the problem was devaluation, but that Wilson ruled out: he remembered how it had been when the Attlee government had devalued, and he didn’t want to face that loss of national prestige or the resentment devaluation had produced, all over again. The problem was that sticking with the pound at an artificially high value meant costs for government which killed many other ambitions, in particular introducing an element of planning and using it to generate growth.Still, the US was pleased Britain hadn’t devalued. It was, however, less pleased that Britain wasn’t sending troops to join its war in Vietnam, but that was a red line for Wilson. He didn’t like wars and he wasn’t inclined to send young British people into harm’s way for a war whose moral grounds many were now questioning and which it wasn’t obvious the US could even win.And Wilson also had to face another grisly chapter in the collapse of empire, when Southern Rhodesia, renamed Rhodesia and under a government headed by the hardline Ian Smith, went for a unilateral declaration of independence (UDI). Again, Wilson however much he disliked seeing Rhodesia hanging on to white rule ignoring its black majority, wasn’t prepared to go to war over the issue. Instead, he tried to use sanctions to bring Smith to his knees, a well-intentioned tactic which simply didn’t work.Illustration: The funeral cortège of Winston Churchill winding its way through London. Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

1 Juni 14min

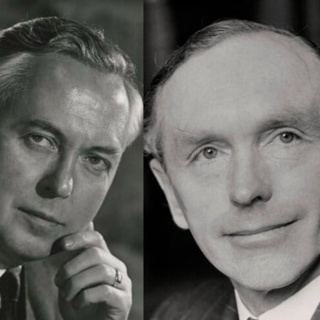

244. Harold gets Home

Here we’re focusing on the changes that took place in Britain after Supermac (Harold Macmillan) stood down as Prime Minister.A lot of how that went depended on the Opposition formed by the Labour Party. Initially it was led by Hugh Gaitskell from the right of the party, with Aneurin Bevan giving him a bad time from the left, while a serious threat was growing from Harold Wilson, formerly of the left which he’d deserted, now of the right which wasn’t sure it could trust him. An object of suspicion across most of the parliamentary party, Wilson was nonetheless appreciated for his ability and for his excellent rapport with voters.Then two key figures died. Bevan, the man seen by so many, for so long, as the leader in waiting, died in 1960. Then, in 1962, it was the turn of Gaitskell himself. All of a sudden, the way was clear for Wilson to forge ahead. Though not fully trusted by either wing of the party, both saw him as something of a least bad option – the left felt he at least had roots amongst them, the right that he'd at least worked with Gaitskell. Wilson secured the leadership with exactly as many MPs voting against him and voted for him, winning only because neither of the other two candidates could take more votes than he did.Wilson showed his skill in the last months of Macmillan’s government, giving him a bad time over such matters as the Profumo scandal. Over that row, Wilson played his cards with great intelligence, enhancing his stature while Macmillan lost his credibility and eventually stood down. He was succeeded by Alec Douglas Home (pronounced Hume), cheating RAB Butler of the prize yet again.As a result, both main parties went into the 1964 general election under new leaders. Home gave Wilson a heck of a run for him money, but in the end Labour won though by a painfully small majority in the Commons. So small that Wilson would be under constant threat of being brought down if a small number of his MPs turned against him.It was clear there would have to be another election pretty soon.Illustration: Harold Wilson by Walter Bird, 25 May 1962National Portrait Gallery x45598, and Alec Douglas Home, unknown photographer, circa 1955, National Portrait Gallery x136159Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

25 Maj 14min

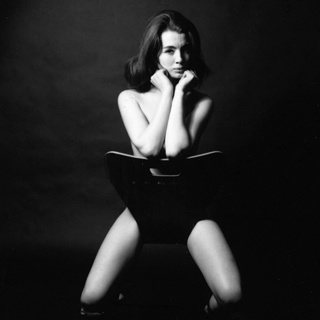

243. Sex, spies and a slippery slope

Last time we looked at the continuing disintegration of the British Empire. In this episode we look at two other key aspects of Macmillan’s foreign policy, Britain’s relations with the US and with potential European partners.Towards the US, what the experience confirmed is Britain’s declining influence and its increasing dependence on, and even subordination to, American policies. Towards Europe, Britain became directly hostile towards the European Economic Community (EEC), trying to build a rival to it in the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). As it became increasingly clear that this was never going to really fly, and as the British economy weakened, Macmillan found himself having to swallow his pride, reverse his position and apply for membership of the EEC after all. To the government’s shock, the perception of Britain as increasingly dominated by the United States led to the French president, Charles de Gaulle – never an Anglophile and now increasingly mistrustful – applying the French veto to British accession. To top all that, Macmillan’s increasingly battered and unpopular government was further hit by a series of three scandals: John Vassal was found to be an Admiralty employee spying for the Soviet Union; Kim Philby who Macmillan had backed against suspicions that he was a Soviet spy confirmed that he actually was by defecting to Moscow; and the scandal around Christine Keeler and the Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, did even further damage to the government’s credibility.By October, Macmillan could stand it no longer and, genuinely not well, he decided to resign as Prime Minister on health grounds.This episode runs a little longer than most, because it also mentions the new German translation of the podcast. It’s available at:https://open.spotify.com/show/08M357CvtiWJsnEGyxitco?si=64613c2919df4a27Illustration: Christine Keeler 1963, photograph by Lewis Morley. Keeler claimed that she wasn’t actually naked. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London/Lewis MorleyMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

18 Maj 15min

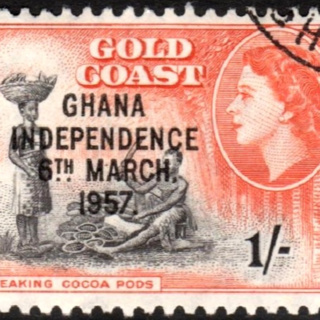

242. A wind of change driving the retreat from empire

‘The wind of change’ was the other famous phrase of Harold Macmillan’s, along with ‘You’ve never had it so good’. It came in a speech in which he talked about how a movement had grown up in many countries, and particularly in Asia, for nations previously dependent on others to break free and become self-governing. Now, he told an audience in South Africa, a wind of change was blowing through Africa as similar, entirely legitimate nationalist aspirations were spreading from country to country in the continent. And it was. Ghana was the first sub-Saharan African colony to win independence, but it would be followed by many others in relatively quick succession. Some went easily. Others went after ugly incidents, notably in Kenya, where bloody fighting led to the use of torture and killings on both sides before the country achieved its freedom from the British Empire. And then there was South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (today’s Zimbabwe) which clung on for several more decades to white minority rule. They too got away from imperial rule, but there was no sense of their granting freedom to a majority – only to a tiny, elite minority. An elite which, during his childhood, even included a man whose name has become a household word around the world: Elon Musk. Illustration: A stamp with Queen Elizabeth II’s head from the British colony of Gold Coast, overprinted with Ghana Independence, marking the nation’s transition to self-government. Public DomainMusic: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

4 Maj 14min

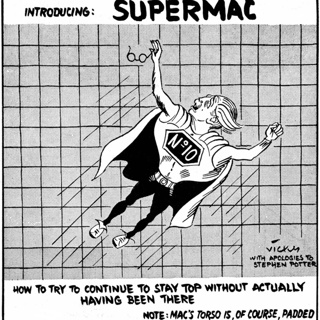

241. Supermac: you've never had it so good

Macmillan overcame the terrible legacy of the Suez catastrophe and, running an economy focused on growth to fund increasing living standards, giving him the opportunity to annouce that people had never had it so good. That reflect both a genuine concern with eliminating poverty and as an effective electoral strategy, pulled off the trick by increasing the Conservative majority in its third consecutive general election win in 1959.Meanwhile, in the Labour Party, in opposition, the left-right split was causing serious dissension, with Nye Bevan leading the left and winning great support for his brilliance and his charisma, but a lot of criticism too for the damage done by views that were sometimes extremist. His group of troublemakers included the young and ambitious Harold Wilson. He, however, when he realised that aligning with the left wing was getting him nowhere, drifted rightwards, ending up by taking Bevan’s seat on the Labour Shadow Cabinet instead of backing his resignation from it. He then supported the rightwinger Gaitskell’s campaign to become Labour leader against Bevan. Macmillan found himself facing Gaitskell and Wilson in opposition to him as his continued dash for economic growth, alongside fear or inflation and pressure on the currency, led to his alternating between periods of economic relaxation and periods of retrenchment. Gaitskell and Wilson denounced ‘boom and bust’ economics.Things were beginning to turn nasty for Macmillan. But we haven’t seen how nasty yet.Illustration: Supermac as seen by Vicky Public Domain.Music: Bach Partita #2c by J Bu licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivatives (aka Music Sharing) 3.0 International License

27 Apr 14min